Dirt.

This clay season, old prejudices are a welcome sight, situating us within a familiar ballpark of experience. But what do they all mean?

Hola a todos.

Dirt season is back.

That means Annual Sneaky Tennis Urge #1 is also back:

To talk about clay like it’s a great slum overdue for demolition.1

The angel on our shoulder had a year to zone this disstrack out, but now the devil is back.

Why does this keep happening?

Well, I’ve unearthed three reasons so far.

Reason 1: Old racquets and traumas, internalized.

Look to Adam Sandler. Don’t look to your dad. Your dad is a liar.

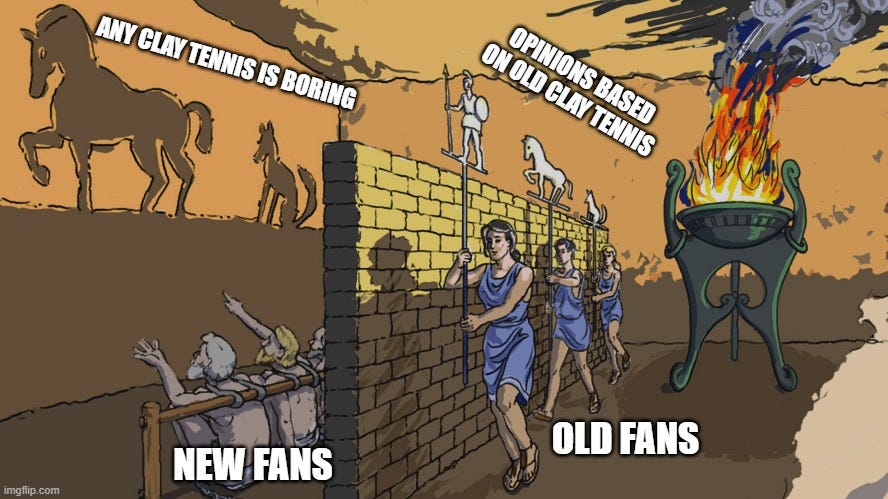

Most of this urge comes from older tennis fans and their long-standing prejudice against the tragicomic clay court matches of the 1980s. They’ll slot modern clay court tennis as “too slow” based on a crappy memory of pre-modern-era clay court tennis, and they’ll influence you into believing it is slow in that strange way overaged devotees make underpowered generalizations sound powerful.

Pull up a chair one afternoon. Test your dad.

Circa 1984, the carbon-fibre revolution in racquet technology was struggling through a hesitant puberty. 75-mph shots (the average shotspeed these days) were possible but improbable. Employing heavier materials, smaller headsizes, and big grips, the erstwhile knights of tennis’s Middle Ages couldn’t afford the elfin strokes of today’s players. They were still figuring out the tech.

From 1975-1982, some of these professionals were forced to transition through three (!) racquet materials:

Wood

Steel

Graphite

Three materials of widely different stiffnesses and densities.2

That's like going from a Nokia 3300 to a iPhone 2 to an iPhone 14 inside eight years.

Savvy tennis fans look back on that 1975-85 tennis cohort like we’ll look back on Gen Y’s prefrontal cortexes calender-rolling through traditional television, Web 1.0, and Web 2.0 from the 1990s to the 2020s.

With a sense of awe and pity.

Anyway, the point is...

…the old guard of boomer and Gen X fans, squinting at grainy, convex-screened televisions, had to pretend to respect the stroke-zombied daymare that was Wilander and Lendl on clay. For nearly a decade. God forbid they aired out what everyone was thinking: that this was the funeral of the sport, shovel by slow shovel of dirt on coffin. What skill could there possibly be to this other than putting the other guy to sleep? No one respects the tortoise in Aesop’s fable. No one. We all just pretend to.

“Dad, did you watch this and really think it was the best TV could offer at the time?”

Watch the 66-shot rally from 1:20 - 3:20 to get a sense of the 1984-racquet’s limitations, and how clay ruthlessly exposed it.

Push. Push. Moonball. Moonball. Push. Push. Moonball. Moonball. Push. Push.

In the end, Lendl uses the winning dropshot much like Alcaraz does these days: off the fear of his big forehand. But his forehand has a tinier sphere of influence than the Spanish phenom’s, so he couldn't use it as wastefully as Alcaraz does these days. In the point following the 66-shot rally, Lendl’s (fed up?) two-punch return combo makes you wonder why he wasn’t doing that in the point before (3:30 - 38).

But, the thing is, his forehand was an outlier for its power.

It was the reason he was the best player of the 1980s.

It didn’t come cheap.

Holding his Adidas Graphite GTX Pro in a clunky L5 gripsize that isn't very conducive to generating racquet-head-speed, he had to pick rare moments to unleash it. And he was swinging only 74 square inches of real estate at a relatively high (for now) swingweight of 365. He didn't swing big at every ball because even he, the crack shot of that era, was liable to shank it and send it into a booing French mouth.3

Meanwhile, Alcaraz uses a generous 98 square-inch headsize, a flexible L4 grip, and a breezy-light 323 swingweight.4 He bombs down 90-mph forehands as if they were free ammo sent from the tennis gods. Gratuitous, samsonian violence.5 Lendl is standing inside the baseline. Alcaraz is standing two metres behind the baseline. But Alcaraz's second forehand reaches the opponent's baseline within the same duration since the serve.

Yeah, duh, tennis is now almost twice as fast as it was in 1984. But my point is that if fans of the 1980s had watched someone less-skilled than Lendl and Wilander, the two best claycourters of that era, the tennis would have devolved to an even slower and less-thought-out mess. They’d watch lo-fi gameplans where points concluded with the gawky “short-shorts” dude charging the net in desperation, flailing, and missing.

So, we can’t really blame these two for creating those clay court farces. And we also can’t underestimate the extent to which these farces traumatized our predecessors. For decades, Moonball Men stuck in the Boomerbrain’s crevices like wet mud. Then, our dads and moms couldn’t keep pretending that what they’d seen was fun. Their pretense finally broke.

The rest is history—the history of sloppily communicated sports folklore.

A Plato’s Cave of misshapen shadows, projected by old men.

They can't, and they won’t, admit that modern clay court tennis is fast, in fact, perfect—a Goldilocks Zone for the new racquets.

Djokovic and Nadal could exchange six 80-mph balls over an 8-second flurry today, but many of you older fans out there will fixate on Bautista Agut infuriatingly bunting backhands back at an angry Medvedev. You’ll fixate on the bad aspects of modern clay court tennis, and you’ll feel bad. An especially cautious modern player might moonball for only one especially scoreboard-pressured points, and you’ll moan about clay being unwatchable. But deep down, you know it’s not the clay that’s hurting you, but the weird stuff that happened on it decades ago—on account of racquet tech.

It’s a bit like how a whole generation didn’t want to watch Adam Sandler’s rottenly-good Uncut Gems (2019) role because they found most of his work dumb in the 2000s. Whenever you have to talk about it, you tell people that clay court tennis stinks because it’s too slow compared to the other surfaces you’ve always loved. Sandler’s dumb-but-poignant Click (2006) was actually meant for people like you: Stop lying to yourself. Be mindful of the time when it’s evolving past your love for it. You can’t fastforward to the grass season.6

So that’s one reason why we act too cool for clay.

Reason 2: It feels like poverty, no?

James Joyce was petrified of bogwater throughout his young adulthood. Imagine us.

Then there’s a second, shallower reason for Annual Sneaky Urge #1.

Yellow-brown clay courts just look so poor.7

To me, they’re colour-adjacent to cricket maidans bordering Bombay’s jhopadpattis. There, boys defecated in the pre-dawn hours, too early to be seen by most eyes five storeys high in the overlooking middle-class apartment buildings, but just in time for the early-rising schoolchildren there.8 I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that, for some of us, clay courts trigger an aporophobia toward our past selves, reminding us of a childhood’s poverty of choice. For me, within the labouring rebirth of India’s economy in the 1990s, the lack of playing space and the messiness of child group politics meant we often had to go looking for a ground in squalid neighborhoods we weren’t totally comfortable with.

Even if you aren’t within the same ballpark—shitty cricket pitch?—of experience, classism gets you in some way or another. You’re probably running away from a poorer archetype to be “better” than it. You’re running toward a richer archetype, so it stops making you feel “worse” for who you are. Then you draw new lines, your new standards. You won’t hang with some of the people you used to hang with before. And it’s okay.

Then, when you see one of the uglier clay courts, some bog monster breaks into your brain’s library, and rummages in the shelves titled ‘Power and Logic.’ And that slip in your consciousness gives you a faint whiff of a memory of a memory.

This memory is awfully similar in each of us: a parent’s forced comparisons with a more talented cousin, a rich kid sprinkling a sandpit’s contents into your hair and getting away with it; an unexpected tumble ruining a rare T-shirt that you couldn’t afford otherwise; snot-nosed boys shouldering you into chai-coloured puddles; overworked mothers raging as wet topsoil is transferred onto their shiny, new floor tiles.

I’m not saying you’ll remember all this as you watch a clay court match, or think “Clay courts poor, me want better.” It’s just that spending your time with anything that doesn’t seem to meet your shiny, new standards puts you off, especially if you’re new to tennis. “Netflix’s ‘Beef’ sounds more my speed for Saturday night instead of this dirt-stained moan fest.”

This is probably what clay season feels like to many uninitiated viewers within the social architecture of online-streamed sports. It’s a 50-50 call that you don’t want turning into a crapshoot of your time. Because it might, just might, trigger those barely perceptible atavistic fears of a life where dirt, dirty boys, poverty, and entropy ruled.

Reason 3: Social media’s clackety-clackery.

It’s a carnival of schadenfreude out there. And that’s how it should be.

The last reason?

It’s a social-media-community evolution of Reason 2.

Bad optics, oneupmanship, cliques, and good old geopolitics.

It’s confusing if you’re new, but it’s fun if you know what’s happening.

One of the more pointless arguments during clay season revolves around line calls.

Clay courts are so dirty that even technology can’t figure them out. The seven Hawk-Eye cameras on the periphery miscalculate the ball mark by a whopping 5mm, as puffs of clay confuse their computerized hivemind. Hawk-Eye isn’t even sanctioned for line calls on clay. It’s more like a match-analysis gadget for coaches, recording important variables such as where in three-dimensional space their player’s racquet contacted the ball, or the number of times Daniil Medvedev said “dirtballing dog” under his breath.

And yet, officials think it’s a good idea for TV broadcasters to reveal these inaccurate Hawkeye line calls.

Clay season’s optics suffer for this bit of broadcasting stupidity.

Naturally, someone new to the tennis-watching world would think, “Why is that boneheaded umpire not referring to the Hawk-Eye graphic?” And they won’t get satisfactory answers. Because the only reason ATP officials persist with a system that fails on clay is a long-standing business contract with this Sony technology. Perhaps Hawk-Eye also aids their “Controversy is good for the sport” ploy; ball mark controversies send viewers into a commenting frenzy over who was right and who was wrong, multiplying TennisTV’s tweet impressions.

As the sun sets on another comedy of unforced errors, the exasperated brotherhood of tennis hipsters9 finally educates everyone and their mothers about Hawk-Eye’s uselessness on clay, and of its low-error Spanish rival, FoxTenn.

Clay season is also defined by Anglo tennis players losing.

Anglo tennis players generally suck on clay.

In tandem, Anglo tennis fans10 will begin to bitch about the clay-loving folkways of what they imply are less important tennis cultures. It’s like a globally-scaled-up version of our overwhelming, psychological need for gentrification (see Reason 2).

Some of you guys wouldn’t even mind adding a Mexican Filter11 to the whole scene. Swarthy, sweaty bullies will win ATP 250s on the surface that you hate; American TV taught us they look like someone working for a drug cartel. And you’ll hint at that analogy without really compromising yourself, hah. As a secret member of the global clique of clay-hating, techno-fetishists plugged into this Matrix of Visual Consumerism, you’ll cunningly pose all these bad optics as a reason for clay court tennis’s future abolishment. It's beautiful in its cunning.

Meanwhile, Anglo podcasters will mock 15-shot rallies painfully constructed by men from Hispanic nations. Said podcasters will be sent a gift hamper of likes and retweets from the mostly-Anglo online village that is Tennis Twitter, in honour of their progressive snark.12

This Tennis Twitter village, which usually makes it a point to fight for the Little Guy, and to research all his little talents and ambitions, finds Annual Sneaky Urge #1 a guilty pleasure. Because, behind all our woke makeup, we privately think this is like one of those stories where provincials get rich off tobacco, codfish, cocaine, you know, something less upper-classy.

Something like clay.

Do you remember the onion knight from Game of Thrones? The other nobles didn’t care to give him the time of day. Because he’d earned his social status off playing a dirty game: smuggling onions into seaside castles to save usurpers like Stannis Baratheon. Who cares if he had the skill to navigate ships between treacherous rocks on moonless nights? He’s a parvenu.

He knows it.

And so do his sons.

In the books, he laments that they don’t look with pride upon House Seaworth’s banner, emblazoned with a sigil of an onion on a ship’s sail. To him, the onion means true grit. But to them, it’s like our dirty playgrounds, crumbling apartments, and Joyce’s bogwater—a motif of a squalid past they don’t want to remember.

[My sons are] lowborn, even as I was, but they do not like to recall that. When they look at our banner, all they see is a tall black ship flying on the wind. They close their eyes to the onion.

— George Martin, A Clash of Kings

In the tennis world, a modern-day claycourter from Quito or Seville is archetypally an onion knight: famous for what is seen as a dirty, smelly game that stings the viewer’s eyes. Their armada-on-dirt can raise a banner bearing a sigil of yellow-green balls on orange courts, but it won’t mean much to the mainstream fans, the Anglos.

Meanwhile, our Anglo tennis pros are the Theon Greyjoys, who continue flopping through the clay season, waiting out April to June, waiting for hardcourts, and sitting pretty in bachelor pads offline, babysat by media biases online. 13

One “special” Anglo tennis pro, a gamer-slash-gangsta, a Malaysian-prince-slash-everyman, an oxymoronic moron confused about his place in this global story, won't even attempt the clay season, choosing to couchpotato in Canberra—and mock the pack of double-surnamed "dirt rats" earning their livelihood on the dirt.

Our tennis hipsters will, once again, have to educate us about superior, low-error Spanish courtcraft.

Dirt season is back.

That means, despite all these self-defeating curiosities and homegrown fears, modern tennis will finally and beautifully rediscover its complete expression.

On the only surface that can take it.

To make the most of it, we just have to know who to watch. I’ll—probably—write a post about fun players to watch on the clay, this week.

Thanks for reading!

The desire to gentrify the tennis-watching space with fewer clay court tournaments isn’t new. It’s been going on since the 1970s, when clay was the most played surface on the men’s circuit—albeit, not at the majors. We’re so deep in the Matrix, we consider the Monte Carlo Open (April) the start of the claycourt season, even though the Golden Swing (February) is its real start. The Golden Swing is a lower tier of clay court tennis, played in South America, that is usually deemed not important enough for mainstream tennis fans.

These days, players barely even modify 10 grams on the same racquet.

There is another complication called gut strings. But that’s for another time.

Alcaraz’s racquet specs are verified by stringer folk and other nerds at Tennis Warehouse, which you can find on this Google Sheet. They’re easily less clunkier than Lendl’s. The main difference between Lendl’s and Alcaraz’s eras is that manufacturing versatility now permits materials engineers more freedom over variables such as mass distribution, stiffness, and additives. 40 years of experimenting have allowed them to perfect what was only beginning in the 1980s (Racquet tech has been in a stasis for the last 15 years, though). And the players have also been experimenting. There wouldn’t be an Alcaraz without forehand experiments by Lendl, Sampras, et al.

What the hell? Google says “gratuitous” is “lacking any good reason or purpose and often having harmful effects”? I meant it in its original sense: Alcaraz’s forehand is “freely given” by the gods and their carbon composite technology. Web 3.0 needs to stop Google from oversimplifying language.

And now grasscourt tennis has gone past that tipping point, becoming unbearable to watch on the men’s side, where 130-mph serves kill the spectacle. Ironically, clay earned the Goldilocks Zone of space-age racquets.

Yellow-brown clay courts are the predominant variety of clay courts, seen in Rome, Barcelona, and the Golden Swing. They tend to look “poorer” than the oranger clay courts at Roland Garros, Monte Carlo, and Madrid, at least within my own subjective nonsense.

There’s often a lack of toilets in the low-cost settlements; plus, it’s breezier and less smelly in an open area.

To know more, refer to the Tennis Hipster Handbook, at:

Anglo = my informal heuristic for anyone from the U.S., U.K., Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Loosely, someone from the dominant, English-speaking western culture. Regardless of skin color.

Re “Mexican Filter”: Not sure if my reading audience includes new tennis fans, but Anglos see clay as a surface where Mexican, South American, and southern European players excel. In other words, the Hispanic and Latino crowd are supposed to own clay, after which “they go back to being irrelevant.” But this isn’t even strictly true, as northern, eastern, and western European players also excel on clay (with the exception of the U.K.). So why do the southern European and South American players get most of the flak for clay court prowess? Probably comes either from colorism (they’re slightly darker, olive-skinned)… or that many tournaments are played in South America… or just regular old sports fan hate!

… and I will earn “snark points” in the teeny-weenier village of my mutuals on Twitter and Substack. Meanwhile, we’re all low-key ashamed that we haven’t researched these Hispanic players enough to say or write something meaningful about them. Bautista Agut is on a horse.

Not that that would change much for the post-Wimbledon hardcourt season, when only a crownless, careening Ent-mutt replaces one of the all-conquering, all-European supergroup I will describe in a later article (his surname rhymes with “bigforeheadvedev” and we all wish he had a bigger forehand). Anglo men’s tennis will not see slam winners in the generation of Taylor Fritz, Nick Kyrgios, Frances Tiafoe, Cameron Norrie, and Jack Draper. Tiafoe was inconsolable after losing to Alcaraz in the 2022 U.S. Open semifinal, because he knew that would be his only chance to win a slam. (Also, Brits are not Europeans when it comes to tennis.) Felix Auger-Aliassime and Denis Shapovalov, who also fall under my loose definition of Anglo, might win a slam. But I’m not confident.

Same feels of poverty on yellowbrown courts😂. Orange-red color somehow adds to the grander

brilliant! 👍